バートンさんのこと

松岡享子 翻訳家/児童文学研究者 東京子ども図書館名誉理事長

1964年3月中旬、バートンさんは、一人でひょっこり日本に来られました。石井桃子さん宛のお手紙には、それまでに何度か「あなたの美しいお国をお訪ねしたい」と書いていらしたそうですが、決して気軽に旅をなさる方ではなく、むしろ旅なれない、ご本人のことばを借りれば「臆病な旅行者」であったバートンさんが、このとき、なぜ日本まで足をのばそうと決心されたのか、今から思うとふしぎです。私はその頃折よく失職中で、毎日無聊をかこっておりましたので、バートンさんのご旅行のお供をお引き受けすることになりました。3月20日に東京を発ち、沼津、下呂、高山、京都、奈良を経て、4月3日に再び東京に戻るまで、ちょうど二週間の旅でした。この間、文字通り朝から晩までバートンさんと行動を共にしたわけですが、その経験を通して私が感じたことを、ひとつ、ふたつお話してみようと思います。

日本の旅館に泊まって温泉に入ってみたいというバートンさんの御希望で、下呂に三泊いたしました。うち一日、お天気のいい日を選んで高山に行きました。夕方には汽車でまた下呂に戻ったのですが、私たちが駅前に出ますと、何台も並んで客を待っていたタクシーの間から一人の運転手さんが「やあ、お帰りなさい」といわんばかりのにこにこ顔で私たちに近づき、私たちを自分の車に案内してくれました。私がはてな・・・・と思っていると、バートンさんは「この運転手さんは、今朝私たちを駅まで送ってくれた人でしょう」とおっしゃったのです。車が動き出して運転手さんがいろいろ話しかけるまで、私にはそれがわかりませんでした。「よく憶えていらっしゃいましたね」と感心する私をいたずらっぽく見て、バートンさんは一言、「画家の眼(artist’s eyes)」とおっしゃいました。自分の眼は画家としてしっかりものを見るように訓練されているので、一度見た人の顔はなかなか忘れないというのです。

実際、バートンさんとご一緒して私が一番痛切に感じたことは、バートンさんがものをよく見る方だということです。バートンさんはご旅行中ずっとスケッチブックをはなさず、「これは私のカメラです」とおっしゃりながら、どこででもスケッチをなさいました。バートンさんが一番お描きになりたかったのは、建物でも景色でもなく人間でした。とりわけ赤ん坊をおぶった女の人、腰の曲がったお年寄り、ピッ、ピッと笛を鳴らしながらバスを誘導する若いバスガールなどには興味をそそられたようでした。けれども、その人たちをその場でスケッチなさることは決してありませんでした。「失礼な気がしてその人の前ではどうしてもしたくない」とのこと。そんな時はじっと見ていらして、夜、宿に帰ってから記憶によってスケッチなさるのです。よく訓練をされた目によってしっかりととらえられた対象は、時間を経た後でもはっきりとした映像となって甦って来るのでしょう。

こんなバートンさんを見ていて、私は、絵を画くということの一番肝心な部分は、実は画くことではなくて見ることにあるのだと教えられました。沼津の海辺のホテルの窓から入日を眺めていらしたバートンさんが、海の色や松の木のかげが刻一刻変って行った様子を情熱を込めて話してくださったとき、下呂の旅館での雪の朝、ふとんから頭だけ出して、降りしきる雪を眺めながら「なんて美しい!」とくりかえしおっしゃるのを聞いたとき、私はバートンさんが羨ましくなりました。同じ経験でもバートンさんはよく見ることによってずっと豊かなものにしていらっしゃると思われたからです。口を開けば東京から自然が失われていくなどと嘆きながら、現に与えられている自然から、十分には歓びを得ていない自分を思って恥ずかしくもありました。

『ちいさいおうち』を読むと、バートンさんが四季の移り変わりを、どんなに大きないつくしみをもって眺めていらっしゃるかがわかります。また、バートンさんは、フォリーコーブ・デザイナーズのモットーそのままに、すべての作品を、自然(実生活)に根をおろしておかきになりました。最新作『せいめいのれきし』(1962)でも、終り近く、ご自分の家を舞台に、四季の変化に加えて一日のうち朝、昼、晩の変化、そして更に、暁けがたから夜があけはなたれるまでを丹念に描いていらっしゃいます。その絵を見ていると、バートンさんが、そうした自然の動きに対してどんなに深い驚きと歓びを感じていらっしゃるかがよくわかります。

バートンさんはそのよく見える目と無邪気な心で、日本の海を、雪を頂いた山々を、田んぼに美しく積まれたわらの束を、竹の林を、見ていらっしゃいました。奈良、京都のお寺も、東京の道路工事も見ていらっしゃいました。電車のドアーで押し合いへしあいする人々も、道路で何度もお辞儀を交す人たちもごらんになりました。そればかりではありません。パチンコ屋も、コーラス喫茶も、はてはチャンバラ映画までごらんになりました。

バートンさんを考えるとき、なぜかアーティスト(芸術家)ということばよりクラフツマン(職人)ということばが浮かんできます。ひらめきや気分といったものにたよらず、確実にご自分の目と手によってお仕事をしてこられましたし、『ロビンフッドのうた』に見られる気の遠くなるような細かさ、丹念さは、最高のクラフツマンシップとしか言いようがないからです。非凡な才能を与えられた作家が真摯に、そのときそのときの力を出しきって仕事をするとき、そこに時代の力や自然(社会もふくめて)の力も相働いて、頭の中でこねまわしたのでは到底得られない、のびやかさと深みのある作品が生まれる――バートンさんの絵本は、そういう作品だと思います。

家庭文庫研究会会報38号 1964年7月、月刊『繪本の世界』1973年9月号より引用・再編

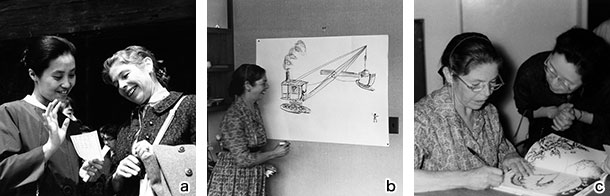

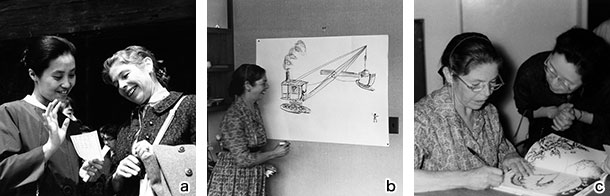

来日時の写真 1964、個人蔵

a. 東大寺にて松岡享子と

b. かつら文庫にて

c. かつら文庫にて石井桃子と

Trip in Japan with Ms. Burton

Kyoko MATSUOKA Translator/Researcher in Children’s Literature Honorary President of Tokyo Children’s Library

In the Middle of March 1964, Ms. Burton came to Japan by herself. She had written to Ms. Momoko ISHII several times that she wanted to visit Momoko’s beautiful country. She was not an easy traveller, though. She was never at ease of travelling. I now wonder why Ms. Burton, who called herself “a timid traveller”, decided to come all the way to Japan at that time. Anyway I was fortunate that I had lost the job at that time and could accompany her during her trip in Japan. It was a two-week trip, leaving Tokyo on March 20 and returning on April 3 via Numazu, Gero, Takayama and Kyoto. I was with her literally from morning till night. I will tell you some of my experience at that time.

Ms. Burton wanted to stay at a Japanese inn and we decided to stay at Gero three nights. On a fine day during our stay there, we had excursion to Takayama and came back to Gero by train in the evening. When we came out of the station, we saw lines of taxis waiting. A driver came out between the taxis and approached us with a big smile on his face communicating, “Welcome back.” He led us to his car. I was not quite sure what had happened, but Ms. Burton said, “This driver is the one who drove us to the station this morning.” I did not remember this until he started talking after the car started to move. I was amazed, saying, “You have a good memory, don’t you?” She then mischievously said, “Artist eyes”. She told me that she remembered faces of people very well since she was trained to observe very attentively.

It is my impression during this trip that she carefully looked at many things. She always carried her sketchbook, saying that it is her camera, and drew pictures. What she drew most frequently were people, not buildings nor landscapes. It seemed she was interested in a woman carrying her baby on her back, a stooped elderly citizen, and a young female bus conductor who led buses with whistles. She never sketched those people on the spot. She said that she wouldn’t because it was not a respectful thing to do. She observed people very carefully and sketched them from her memory in the hotel at night. She had trained eyes to observe people and objects, which became evident later.

I learned from Ms. Burton that the heart of painting is not to draw but to observe. She watched sunset from the window of the hotel at the beach of Numazu and enthusiastically described to me how the colors of the ocean and the shades of pine trees changed moment by moment. I heard her say “How beautiful!” when she put her head out of the blanket and observed falling snow at the inn at Gero in the early morning. At those moments, I envied Ms. Burton because she could make the experience I shared with her richer and more significant. I felt ashamed of myself since I did not find as much pleasure as she did from the nature, though I frequently complained that the nature had been lost in Tokyo.

“The Little House” revealed her great love for the changing seasons. Ms. Burton made all her works deep rooted in nature (real world life) as in the philosophy of Folly Cove Designers. In her latest book “Life Story”, she elaborately described not only changes of seasons but also those of days, from morning, afternoon and to night as well as changes from sunset to sunrise. Her pictures clearly reveal how deeply she was amazed at and pleased with the changes in nature.

Ms. Burton, with her marvelous eyes and naïve mind, observed sea, mountains capped with snow, bundles of straw neatly piled up in the paddy fields and bamboo bushes in Japan. She watched temples in Nara and Kyoto and road constructions in Tokyo. She gazed at people hustled and bustled in the train at the doors and people bowing many times on the street. Not only that, she visited pachinko parlors, chorus coffee shops and even watched samurai movies.

She always reminds me of the image of not an artist but a craftsman. She did not depend on flash of brilliant ideas nor mood in pursuing her work. She used her eyes and hands to create her works. She showed dazzlingly meticulous elaborations as represented in her book “Song of Robin Hood”, which is nothing but the work of best craftsmanship. When the artist given with extraordinary talent worked to the best of her capacity, coincided by the force of time and nature (including society), unconstrained deep work is created. This is something people cannot produce with mental complication. That is how Burton’s picture books were made.

Excerpted and reorganized from Journal of Home Library Society, vol.38 (July 1964) and monthly magazine “The world of Picture books” (September 1973)

Photographs: Burton in Japan 1964, Private collection

a. At Todaiji Temple with Kyoko Matsuoka

b. At Katsura Bunko

c. At Katsura Bunko with Momoko Ishii